First published in Chieftains and San Patricios

by Mairéid Sullivan

2010, Alternate Music Press

Part 2 review of The Chieftains' 2010 recording, San Patricio.

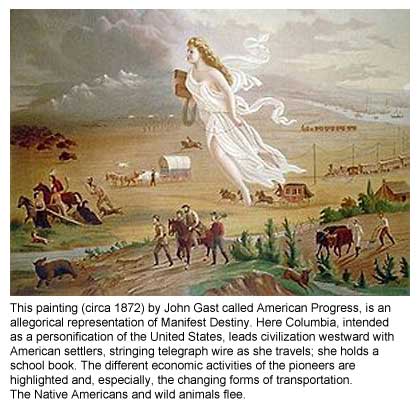

"Manifest Destiny" and the Fighting Irish

By the end of the 1840s, the Irish Famine was in full force:

While the English exported abundant crops, millions of native Irish men, women and children died due to "The Great Famine", and millions more immigrated as refugees around the world (Mullin, 1996; Kinealy, 1997).

In America, the San Patricio Battalion was formed by legendary Fighting Irish refugees who joined the army upon arrival in the USA when they couldn't find employment where "No Irish need apply!", which, according to historian Richard Jensen, was “a myth of victimization”.

They weren't Irish-Americans, as many claim. When they arrived in the USA, they faced the same brutal reasoning that forced them to leave Ireland: that the "Anglo-Saxon race" was superior to all others. They endured relentless bigotry and mistreatment by Anglo-Protestants US Army officers, — essentially the same powers that had perpetrated genocide and confiscation of their native Irish lands, going back to the 12 century.

Why did the Irish change sides in the 1846-1848 US war against Mexico?

Hundreds of Irish soldiers deserted the US Army to join the Mexican side in the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848 when they discovererd they were expected to fight against Mexican Catholics. When they joined the Mexican forces, they were offered payment in land and gold and, most important, they were offered generous hospitality and respect by the Mexican people.

In The San Patricios: Mexico's Fighting Irish (1995), Vista, California-based Irish-American journalist and documentary film maker Mark Day, states:

"In 1846, thousands of immigrants, mostly Irish, joined the US army and were sent with Gen. Zachary Taylor's army to invade Mexico in what some historians have called a war of Manifest Destiny. Dubious about why they were fighting a Catholic country, and fed up with mistreatment from their Anglo-Protestant officers, hundreds of Irish and other immigrants deserted Taylor's army and joined forces with Mexico."

The Irish were led by Captain John O'Riley, from Galway. While held prisoner in Mexico City, Riley wrote to a friend in Michigan: "Be not deceived by a nation that is at war with Mexico, for a friendlier and more hospitable people than the Mexicans there exists not on the face of the earth."

Back to top

"The San Patricios were alienated both from American society as well as the US Army," says Professor Kirby Miller of the University of Missour, an expert on Irish immigration."They realized that the army was not fighting a war of liberty, but one of conquest against fellow Catholics such as themselves."

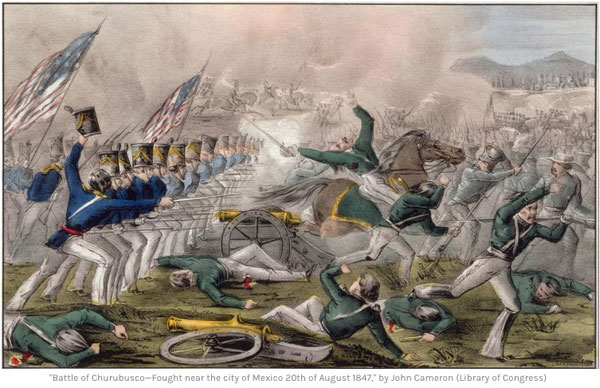

The San Patricios fought bravely, but failed to prevent the US capture of Mexico City, which led to the transfer of all lands north of the Rio Grande to the USA. After the Battle of Churubsco, 83 San Patricios were captured, and 72 were court martialed, 50 were sentenced to be hanged and 16 were flogged and there cheeks were branded with the letter "D" for deserter.

While the San Patricios were considered traitors by Americans, to the Mexicans they were fellow Catholics,—heroes who supported them against the brutal incursions of Anglo-Protestant Americans, who pillaged, murdered, raped their women, and desecrated their churches in order to fulfill their "divinely ordained" Manifest Destiny to expand their frontier to the Pacific Ocean. On Sept. 12 each year, in Mexico, the San Patricios are honored with a special commemoration. In 1993, the Irish launched an annual commemoration ceremony in Clifden, Galway, Captain John Riley's hometown.

Mark Day believes, "Riley"s attitude could serve as a role model in today's multicultural society. In fact, the parallels between the Irish immigrants of the 1840's and today's newcomers from Mexico and Central America should be obvious. Historically, both groups have suffered domination from oppressors who sought to destroy their religion and culture. Both groups have braved dangerous journeys to arrive in America. The Irish crossed rough seas in "coffin ships" laden with diseased and starving passengers, while their Latin counterparts continue to brave barren deserts and freezing mountains, not to mention the barbs of nativists who see them as economic and cultural threats to the so-called "character of America." Mark Day believes, "Riley"s attitude could serve as a role model in today's multicultural society. In fact, the parallels between the Irish immigrants of the 1840's and today's newcomers from Mexico and Central America should be obvious. Historically, both groups have suffered domination from oppressors who sought to destroy their religion and culture. Both groups have braved dangerous journeys to arrive in America. The Irish crossed rough seas in "coffin ships" laden with diseased and starving passengers, while their Latin counterparts continue to brave barren deserts and freezing mountains, not to mention the barbs of nativists who see them as economic and cultural threats to the so-called "character of America."

That these brave young men named themselves after St. Patrick (San Patricio in Spanish) is interesting: According to legend, at the age of 16, St. Patrick was captured by Irish raiders and taken from his home in England, to serve as a slave to Ireland, until he escaped at age 22, traveled to Rome, and became a Catholic priest. He returned to Ireland as a missionary in 431 AD. Very little is known of his life, but legend has it that his first converts were Irish slaves, thereby linking his mission with the struggle for personal freedom.

Back to top

|